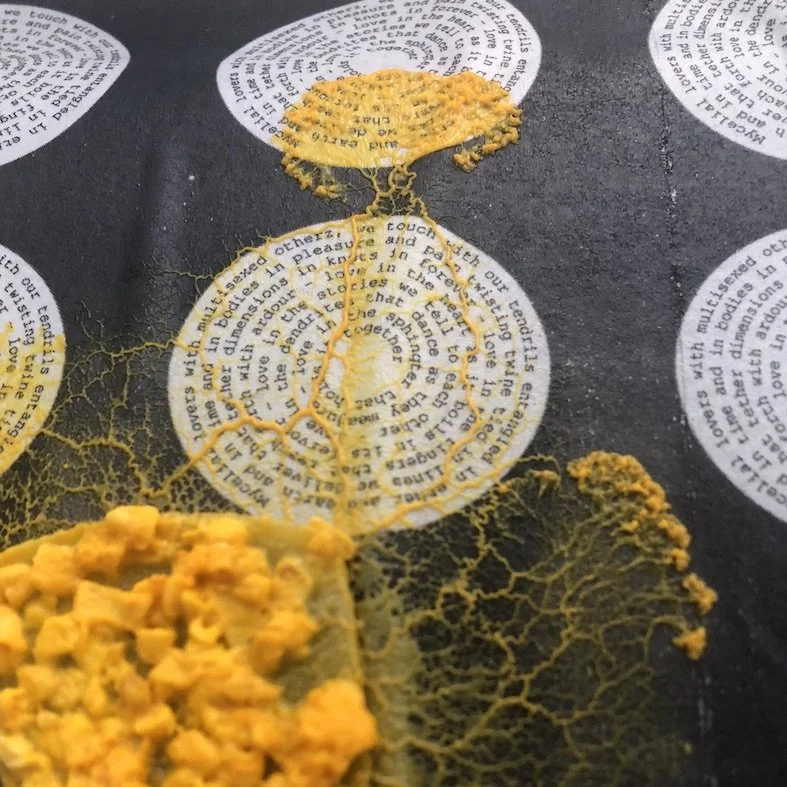

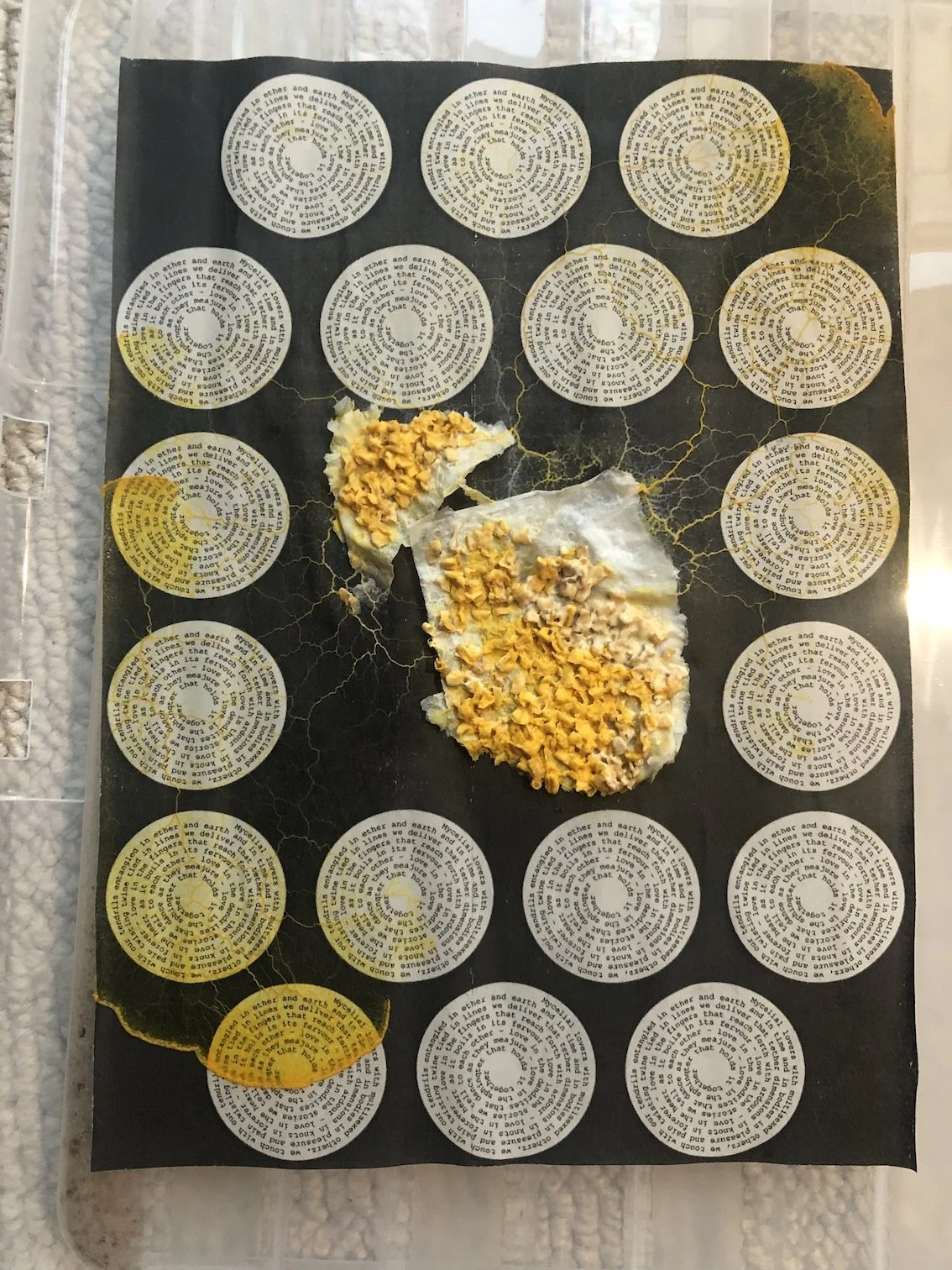

Slime Moulds & Multidimentional Networks

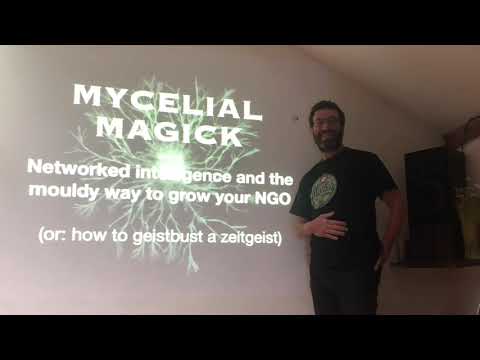

Everyone is talking about mycelia these days, and it’s about time too because they have been around for a billion years or so, and they are amazing.

In the field of “amazing tiny things that network into amazing larger things”, however, my first true love is slime mould, which is older still. I’m particularly enamoured of the amoeba Physarum polycephalum.

I guess that makes me polyamorous.

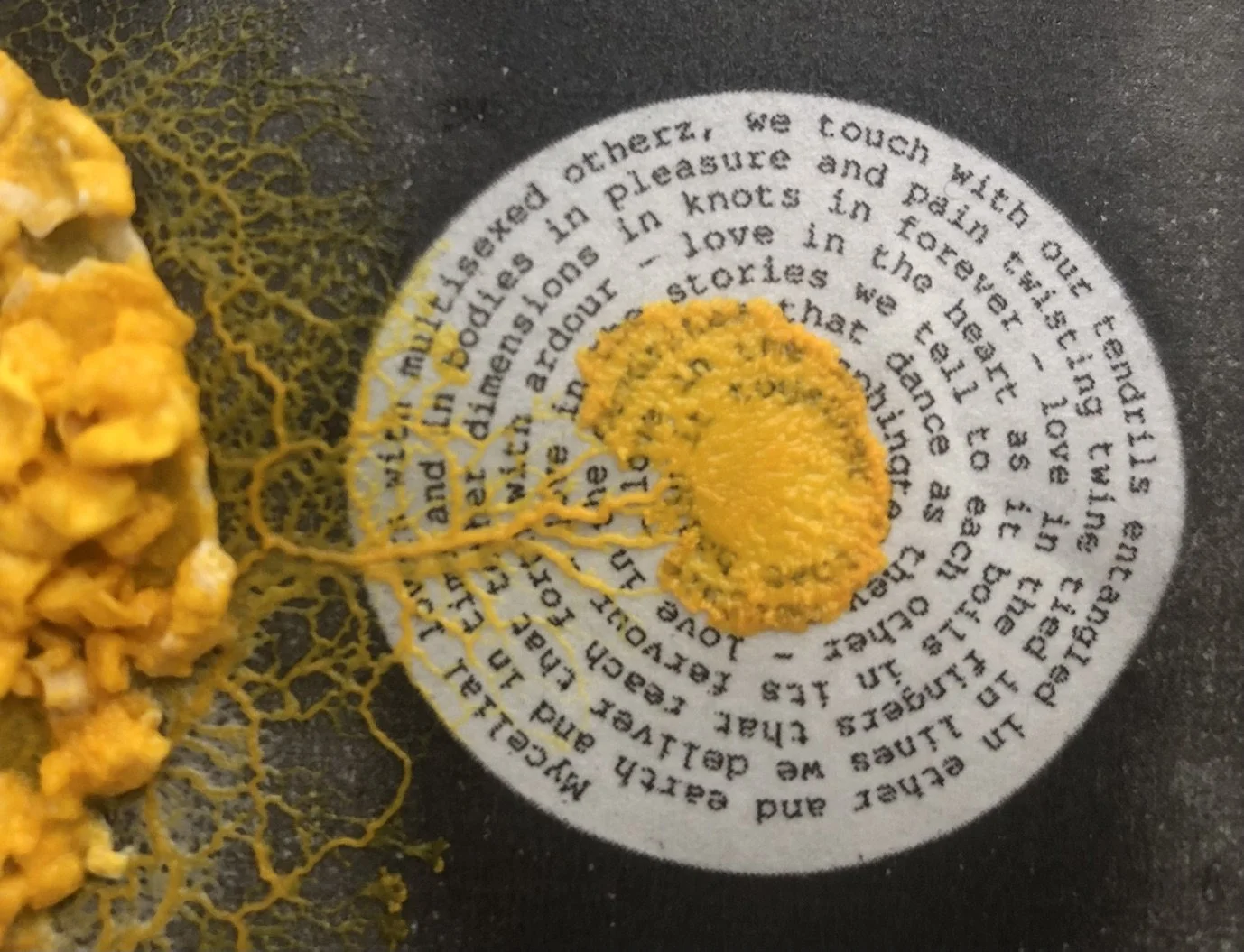

Amy the Amyba making herself comfortable at mine

Amy isn’t quite one and nor is she many, exactly. She evades traditional categories of gender as well as number. She is unambiguously non-binary, despite the name of endearment I use with her; to quote Billy Joel, she’s always a woman to me. This says more about me than her.

Anyway, she’s confusing.

I’m confused, anyway. As well as besotted. Look how she pulses!

She’s not confused at all. As an individual, her decisions are made with the good of the collective in mind (whatever “mind” means in a microscopic speck of goo without a brain or a nervous system). As a collective they behave intelligently, solving mazes and predicting rhythms in time. Amy learns from her environment and teaches what she has learned. They leave food sources for later, showing more prudence than I do when given a packet of biscuits. They distribute resources and information without fake news or censorship. Despite the gooey consistency, the decisions made are consistent, and consistently efficient. I admire her and aspire to her qualities.

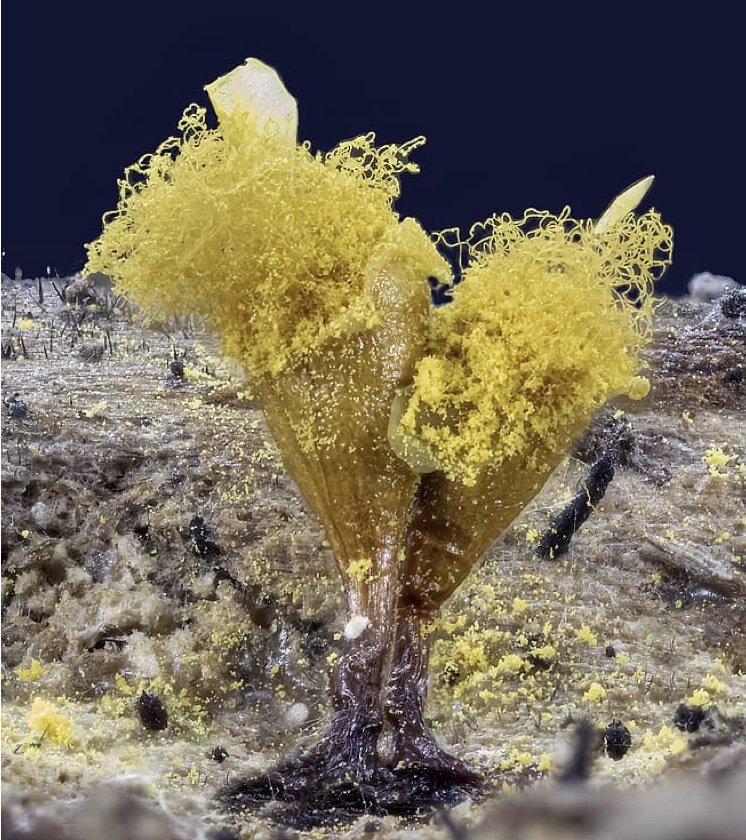

She also responds to a changing environment by working together to build structures that can ensure her survival. When her log habitat begins to dry out, she comes together with others and conglomerates into things that are a bit like mushrooms, and it releases things a bit like spores. They aren’t spores, because they aren’t fungi; but they are clever.

What can an individual amoeba do about her environment changing? Not a great deal; alone, she is at the mercy of the elements and she will dry out. Collectively, however, they build a structure that allows some of them to escape into the air currents, and sometimes onto the wings of passing insects. That way they can find their way to more humid and hospitable places.

Likewise, what can an individual human do about an environment becoming inhospitable? Not a great deal. I feel powerless as an individual when I hear about the desertification of places I can’t pronounce, and my enjoyment of the balmy evening last night was stabbed through by the realisation that we’re a few weeks from Halloween in the Northern Hemisphere (not to mention potentially being a few years away from a major geopolitical confrontation).

What might humans be capable of as a collective?

Any human with an imagination surely daydreams about what the world would be like if we worked together rather than against each other (often with themselves as Führer calling the shots), but perhaps our imagination only takes us part of the way. Does an amoeba imagine the structure she’s destined to construct when she begins to collect herself together?

There is a plan there, in the sense of a template or morphic field that guides the individual to behave in a certain way according to her position. It seems, though, that that template pertains to the field or the species, or maybe its DNA, rather than the distinct imagination of the individual.

In the same way, our capabilities may be utterly beyond our imagination. With a nod to anthropologist Bruno Latour, technologies of communication have allowed us to share our thoughts on ever greater scales, upping our collective intelligence and revolutionising society in the process. Language allowed us to share intelligence between minds, and to think together. The technology of writing allowed us to share intelligence across time, to accumulate knowledge in libraries and draw upon centuries of thinking to respond to current problems. The technology of the printing press distributed those texts widely and much more rapidly, and was a key contributor to the Reformation, the Wars of Religion that reshaped Europe, and the emergence of a scientific world. The world emerging today feels similarly ominous, with threats and opportunities that are bewildering. Those of us who grew up before mobile phones imagined a future with jetpacks and flying cars, but few - including Latour himself - could have predicted the world of the 2020s.

We’ve been through apocalyptic moments before, and if there are still humans in the 22nd century they might make more sense of it. For now, it seems wise to stay humble, to tune into the powers moving the instincts that move us, and to take inspiration from creatures that know how to work together for collective resilience. The plans in the field or embedded in our DNA may involve intelligences as different to us in scale and nature as an insect is to an amoeba.